The beaver species seen in North America is the American beaver (Castor canadensis). Its European counterpart, Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber) is slightly smaller, but plays a similar environmental role.

The North American beaver population was once more than 60 million, but the species was trapped virtually to extinction in the 1800s for beaver pelts. In recent decades, decline in demand and proper wildlife management has allowed beavers to become re-established in much of their former range.

Beavers are the largest living rodents in North America, weighing in at an average of 40 pounds. Beaver are semi-aquatic mammals with webbed hind feet, large incisor teeth, and a broad, flat tail. They have poor eyesight, but excellent hearing and sense of smell. The beaver’s sharp incisors, which are used to cut trees and peel bark while eating, are harder on the front surface than on the back, and the uneven wearing creates a sharp edge that enables ease of cutting through wood. The incisors continually grow, but are worn down by grinding, tree cutting and feeding.

Beaver fur consists of long, coarse outer hairs and short, fine inner hairs. The fur can range in color, but is most of dark brown. Scent glands secrete an oily substance called castoreum, which the beaver uses to waterproof its fur. Beavers are territorial and mark their territory by creating small mounds of mud, leaves, and sticks, and which they coat with castoreum. More susceptible to predators on land, beavers tend to remain in the water as much as possible. They are excellent swimmers, and with valvular nose and ears and lips that close behind the four large incisors teeth, they are able to remain submerged for up to 15 minutes. The flat, scaly tail stores fat, and is used to signal danger by slapping the surface of the water.

Beavers are herbivorous and eat a variety of leaves, shoots, roots, aquatic herbs and the inner (cambium) layer of woody plants. Herbaceous plants are a major component of their diet in summer, but in winter woody plants and submerged roots are their primary food. In Montana, aspen, willow and cottonwood are preferred food, but beaver also eat alder, birch, maple, apple and other fruit trees, dogwood and many ornamentals. Fermentation by special intestinal microorganisms allows beavers to digest 30 percent of the cellulose they ingest. Coniferous trees, such as fir and pine, are eaten occasionally; however, beavers more often girdle and kill these trees for use in dam building material. When the surface of the water is frozen, beavers eat bark and stems from a food cache stored near the entrances to their bank dens and lodges. Food caches are seldom found where winters are mild.

Beavers live in colonies of 2 to 12 individuals. The colony typically consists of an adult breeding pair, the kits of the year, and kits of the previous year or years. A mated pair will live together for many years, sometimes for life. Beavers breed between January and March, and litters of one to eight kits (average four) are produced between April and June. The number of kits is related to the amount of food available and the female’s age. The female nurses the kits until they are weaned at 10 to 12 weeks of age. Most kits remain with the adults until they are almost two years old, and then go off on their own in search of mates and suitable spots to begin colonies, which may be several miles away.

Because of their size, behavior and habitat, beaver have few enemies. Beavers live 5 to 10 years in the wild. When foraging on shore or migrating overland, beavers are killed by predators including bears, wolves, coyotes, bobcats, cougars and dogs. Other identified causes of death are severe winter weather, winter starvation, disease, water fluctuations and floods, and falling trees. Humans remain the major predator of beavers. Historically, beavers have been one of the most commonly trapped furbearers. Mortality from current human activity most commonly takes the form of trapping or shooting for lethal control of nuisance beaver, recreational trapping, and road kill.

Beavers are found where their preferred foods are in good supply---along rivers and in small streams, lakes, marshes and even roadside ditches containing adequate year-round water flow. In areas where deep, calm water is not available, beavers will select sites with abundant building materials and create ponds by constructing dams across creeks or other waterways to create pond and pool habitats.

Depending on the type of water body they occupy, beavers will construct freestanding lodges or will excavate burrows known as bank dens. Lodges and dens are used for safety, and a place to rest, stay warm, give birth, and raise young. Lodges and dens are not subsurface, and have enough air exchange to allow beaver, muskrats, and other air breathing fish and wildlife to breathe while conditions are otherwise limiting. Freestanding lodges are built in areas where the bank or water levels aren’t sufficient for a safe bank den. Lodges consist of a mound of branches and logs, plastered with mud. One or more underwater openings and tunnels lead to center of the mound, where a single chamber is created. Bank dens are dug into the banks of streams and large ponds, and in some sites a lodge may be built over the den. Bank dens may also be located under stumps, logs or docks. Beavers living in cold climates store branches of food trees and shrubs for winter use by shoving them into the mud at the bottom of ponds or streams near the entrance to their bank den or lodge, or may create a floating cache anchored by its own weight or large branches at the top of the cache frozen in ice or otherwise anchored. This latter cache type appears to be most common in larger rivers and other areas with rocky substrate.

Beavers are found throughout North America, except for the arctic tundra, most of peninsular Florida, and the southwestern desert areas. Local abundance may occur wherever aquatic habitats are found. Populations are limited by habitat availability, and the density will not exceed one colony per ½ mile under the best of conditions.

Beaver fur consists of long, coarse outer hairs and short, fine inner hairs. The fur can range in color, but is most of dark brown. Scent glands secrete an oily substance called castoreum, which the beaver uses to waterproof its fur. Beavers are territorial and mark their territory by creating small mounds of mud, leaves, and sticks, and which they coat with castoreum. More susceptible to predators on land, beavers tend to remain in the water as much as possible. They are excellent swimmers, and with valvular nose and ears and lips that close behind the four large incisors teeth, they are able to remain submerged for up to 15 minutes. The flat, scaly tail stores fat, and is used to signal danger by slapping the surface of the water.

Beaver habitat is almost anywhere there is a year-round source of water, such as streams, lakes, farm ponds, swamps, wetland areas, roadside ditches, drainage ditches, canals, mine pits, oxbows, railroad rights-of-way, drains from sewage disposal ponds, and below natural springs or artesian wells. Beavers select habitat with accessible foods, available lodge or denning sites, and usually associated suitable dam sites. They often then modify habitat to their needs by building dens and dams and creating ponds.

Beavers build dams to create deep water for protection from predators, for access to their food supply and to provide underwater entrances to their dens and lodges. Dams are constructed and maintained with whatever materials are available to the beaver near the water’s edge. Examples of dam building materials used range from wood, plant parts, fencing materials, bridge planking, rocks, mud, wire and other metal, sagebrush, cornstalks, plastic, and other materials. The sound of flowing water stimulates beavers to build dams or to repair leaks in them. However, they routinely let a leak in a dam flow freely, especially during times of high waters. Leaking, often derelict, dams are common in active colony sites during the summer months when beaver are not reliant on water to store cached food and are not inhibited by ice in pursuit of fresh near or above the water’s edge.

Beavers keep their dams in good repair and will constantly maintain the dams especially during times of the year when drops in water levels could compromise the security of the dens and lodges or access to cached food. Typically, beaver colonies will build and maintain more than one dam to impound sufficient water for year-round habitat of an area. In cold areas, dam maintenance is critical because dams must be of sufficient height to ensure water depth sufficient to ensure that the impounded water does not freeze to the bottom, which would prevent access to cached food and potentially trap beaver in their lodges or bank dens.

Forage sites are areas where beavers cut trees, shrubs, cattail, bulrush, and other vegetation both for food and building materials. There will be a pile of wood chips on the ground around the base of recently felled trees. Limbs that are too large to be dragged by beaver are typically stripped of bark over the course of several days. Branches and twigs under ¾-inch in diameter are sometimes eaten entirely. Because of this sometimes heavy consumption of the woody parts of the branches, the floor of beaver ponds may be covered with thousands of beaver droppings that are essentially sawdust pellets.

Slides are the paths where beavers enter and leave the water, typically on a bank where their walking and dragging of cut materials creates a trough or “slide.” They are 15- to 20-inches wide, perpendicular to the shoreline and have a slicked down or muddy appearance. In fall, actively used slides will have ice formation in them when temperatures fall below freezing during the night when beaver are most active in cutting and dragging limbs, branches, and twigs. Beavers also construct channels leading to their ponds, which are used to float food—such as small, trimmed trees—from forage sites. With receding water levels during summer, beaver activity shifts toward building and maintaining canals to access new food supplies.

Dam building by beaver creates diverse wetland habitat that increases wetland functions and ecosystem values including maintaining supplies of clean water and providing complex, high-quality habitat for fish and wildlife. Other benefits include sediment retention and mitigating the severity of spring runoff, both of which can improve stream stability and watershed health.

The beaver works as a keystone species in an ecosystem by creating wetlands that are used by many other species. Beaver dams improve nesting and brood rearing areas for waterfowl in ponds and surrounding areas. The increased growth of riparian wetland vegetation provides additional forage and cover for a variety of wildlife such as big game and songbirds. Beaver ponds help store leaf litter and other organic debris in the water and in turn support aquatic insect production, an important food for fish, amphibians and waterfowl. The increased food sources also attract mink, river otter and muskrats. Trees that die as a result of rising water levels behind beaver dams attract insects that are a food source for many wildlife species such as woodpeckers. The tree snags also provide homes for cavity-nesting birds.

Beaver dams and ponds provide important refugia from strong winter flows for fish. They increase the storage of water in headwaters, resulting in a more stable water supply and maintenance of higher flows downstream later in the summer. By providing plenty of woody debris and aquatic vegetation growth in which juvenile fish and hide from predators, beaver dams help young trout and salmon survive their first vulnerable year. They also provide winter pool habitat important to fish.

Beaver dams create wetlands that help control downstream flooding by storing and slowly releasing water, reducing the severity of high stream flows particularly after winter storms and spring snow melt. Wetlands also improve water quality by removing or transforming excess nutrients, trapping silt, binding and removing toxic chemicals and filtering out sediment. Beaver dams and ponds provide an important function of reducing streambank erosion by reducing water velocity and energy, much like waterbars act to reduce erosion on unpaved roads by diverting the downstream water flow. Beaver also recruit large woody debris to stream channels by cutting trees, thus providing additional obstacles to erosive stream flows.

Beaver dams facilitate ground water recharge and help raise the ground water table. This promotes vegetative growth, which in turn helps stabilize stream banks and minimize erosion. In some areas, beaver dams have been a major factor in building up soil in meadows and reducing the impact of invasive vegetation. Damming activity by beaver also effectively restores incised stream channels and water tables.

Beavers can become a problem if their foraging habits or building activities cause flooding or damage property. Foraging activity may result in damage to timber, crops, ornamental or landscape plants. Beaver dams and resulting elevated water levels may jeopardize the integrity of septic systems, roads, or other human structures or land use activities.

Removal of beaver is rarely a lasting solution as other beavers in the area tend to resettle the desirable habitat. In the meantime, if a dam was destroyed, a valuable pond or wetland providing water storage and valuable habitat to many dependent aquatic and wildlife species may be lost. The best approach is to develop a long-term solution that allows beavers to remain in their natural habitat.

Even in environments where beavers are appreciated and tolerated, their activities can become problematic if chewing and dam building damages property or causes flooding that threatens infrastructure such as buildings, roads and railways. There are several options for landowners to deal with beaver issues, including:

Understanding that beavers fulfill an important role in the ecosystem by creating wetlands that provide multiple benefits to a variety of fish and wildlife as well as landowners, a beneficial approach is to beaver management is learning to co-exist with the beavers. The presence of beavers is often seen as a problem when, in fact, the beavers are causing no harm and may be providing important ecosystem benefits. To assess the beaver problem, it is important to consider if the beaver are really causing damage or creating hardship, and then determine the appropriate control action.

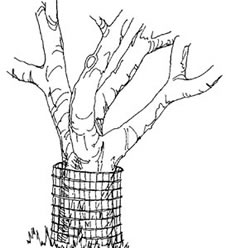

In areas where the landowner or manager is interested in protecting trees from beavers, it is important to note that most, but not all, cutting occurs within 50 feet of the water. While beavers prefer certain tree species, they will cut trees that are most accessible, so it is a good idea to protect desired individual trees. It is beneficial to leave the trees that are already down, so the beavers are not driven to cut more.

In areas where landowners and managers are interested in protecting key trees or stands, the following prevention methods are effective:

Painting tree trunks with a sand and paint mix (2/3 cup masonry grade sand per quart of latex paint) has proven somewhat effect at protecting trees from beaver damage. The animals presumably don’t like the gritty texture. Commercial taste and odor repellents have provided some success, but are more labor intensive as they must be reapplied often, particularly in moist weather. Two repellents that have proven effective in some cases are Big Game Repellent® and Plantskydd®. For maximum effectiveness, these repellents should be applied at the first indication of beaver activity and re-applied a few times per year during dry weather. Repellents are not as effective as properly-installed fencing, but are an option in areas where fencing is not desired.

Removing or breaching dams is an immediate, but usually temporary, solution to flooding problems caused by beaver. In many cases beaver will rebuild the dam, sometimes as soon as overnight. It is often possible to control the pond level to prevent flooding and property damage using a flow device. Before starting any of the following treatments or activities, landowner approval must be obtained. In addition, as these activities typically require some work in wetlands or streams, permits may be required from various local, state, and federal agencies before work is started. Please refer to the Montana Stream Permitting Guide and contact Department of Natural Resource Conservation for assistance.

Beavers create attractive and beneficial habitat by building dams, and often a series of dams, to pool water. When the damming activity creates nuisance flooding, we can still keep beaver and the high quality habitat but prevent damage from flooding by installing flow devices to regulate water levels at beaver ponds. Flow devices allow water to flow through a beaver dam and maintain a desired pond level, preventing flooding of adjacent roads, pastures, or structures. For flow device systems to work properly, you may need to have at least 3 feet of water in the pond area for the beaver to stay.

Example of a Castor Master TM flow device that controls the water level and prevents flooding while allowing the dam to stay intact. The dam in this picture has been notched for installation of the device and has not yet been repaired by beaver. Photo credit: Amy Chadwick

The Castor MasterTM, a design of Skip Lisle at Beaver Deceivers International, is an example of a highly effective device that controls water levels while allowing the dam to stay intact. The design includes a pipe extending through the beaver dam, with the pipe intake protected to prevent plugging by beaver. A flow device such as the Castor Master requires little maintenance (estimated 0. 5- 1. 0 hours/year), and with proper construction the effective life of the device is at least 10-20 years. Material, construction and installation costs range from about $900 to $2500 per flow device, depending on the location, structure size, number of sites at one location, and site characteristics. Other designs, such as the Clemson pond leveler, have proven effective in many situations. In general, flow devices pay for themselves within the first 1–2 years and are an affordable, long-term management solution.

Every site requires a specific design, developed based on beaver activity and likely response, site environmental controls, flood tolerance for protecting property, and proximity of other beaver activity. For sites with ongoing flooding issues, damming in irrigation ditches, and multiple dams we recommend a thorough site review to check project feasibility, develop a plan for beaver management, and define success criteria prior to any installation efforts.

For site evaluation and technical assistance, please refer to contacts on the Resources page. Each site is unique and requires evaluation and custom construction designs. Please see Living with Beavers for more information.

Beavers respond to the sound of flowing water through culverts by damming narrow channels and culverts, which impounds water against roadbeds and causing roads to flood or washout. Plugged culverts are difficult, time-consuming and expensive to repair, and road damaged caused by beavers is a costly problem. Trapping and dam removal is only a short-term solution that requires continual maintenance as beavers will re-colonize and rebuild. Installing a barrier to prevent dam construction is an effective, affordable, long-term solution to maintaining functioning culverts and roads.

A Beaver DeceiverTM is a flow device that protects culverts at roads or irrigation headgates and consists of two filters constructed of sturdy wire and wood posts with a pipe to connect the filters, which maintain water flow through the culvert, reduce the sound of flowing water, and prevent dam construction. This system is an effective solution to address the culvert plugging and provide the benefit of dramatically reducing maintenance costs. These structures are built to last at least 20 years with minimal maintenance. Cost savings provided by these structrues were documented in a 2006 study funded by the Virginia Department of Transportation, which compared the cost of flow device installation to traditional maintenance (culvert unplugging, dam removal, trapping) and found that every $1 spent on flow device installation saved $8 in maintenance costs. See Further Reading for more information.

For all flow device systems, each site is unique and requires evaluation and custom construction designs. Please refer to Living with Beavers or technical assistance for additional information on flow devices.

Beaver trapping tends to be an expensive and short term solution, as new beavers will relocate to the trapped area, often within 1-2 years. Beavers are classified as furbearers in Montana and you must have a license or damage permit to trap legally. If trapping is the only solution, please contact Montana Trapping Association for expert assistance. Additionally, many of the Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks officesalso maintain a list of trappers who can assist with live trapping efforts and can arrange trapping.

Relocation of beaver is appropriate in extremely rare circumstances and requires completion of an Environmental Assessment along with approval by the Fish and Wildlife Commission.

Technical Assistance

Montana contacts with experience in non-lethal beaver management:

Torrey Ritter

Elissa Chott

Amy Chadwick

Stephen Carpenedo

Other contacts

Additional Resources