Big Hole Pronghorn Migration

Outdoor Report

FWP captured and collared several pronghorn near the Big Hole Valley as part of a statewide migration study. Here's a look at one doe's 80-mile migration.

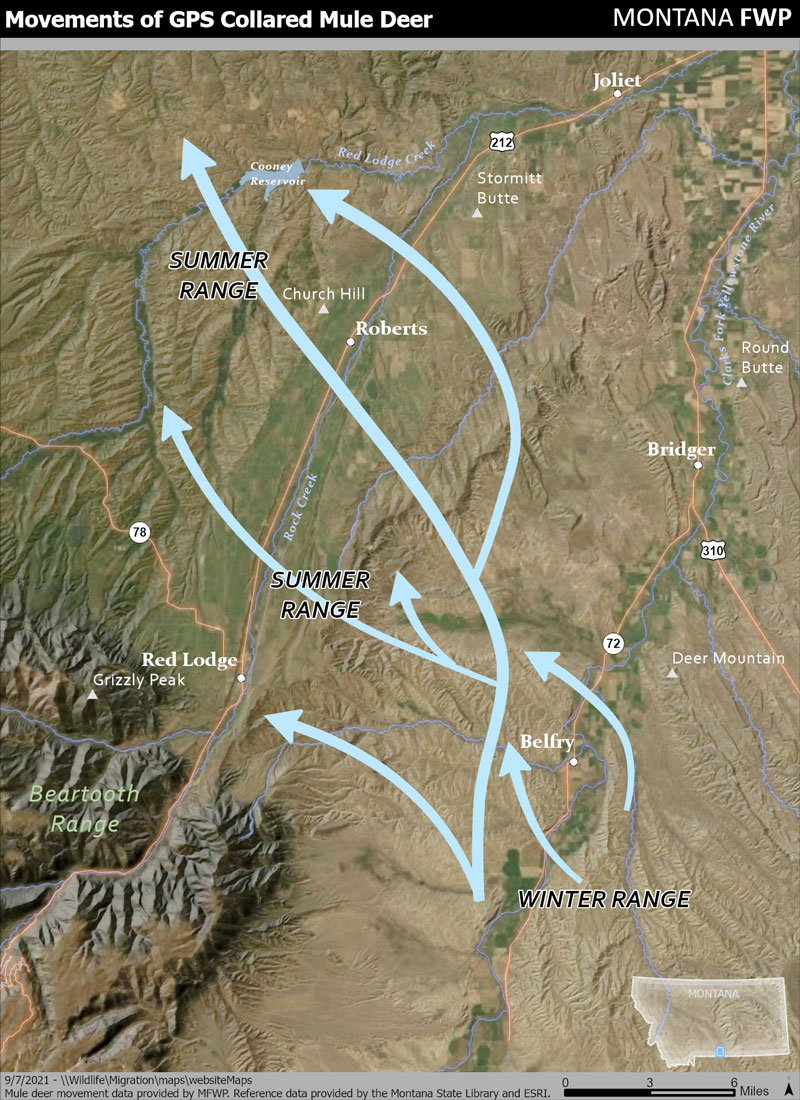

Migrating can mean thousands of miles across continents or much shorter movements up a mountain or between ponds. Not all animals migrate, but for those that do, the strategy can arise for a variety of reasons. Animals may migrate to find nutritious food, to avoid risky conditions, or to compete for limited resources. For example, ecosystems like the arctic or high elevation mountains of Montana can produce excellent food during the summer months, but winter conditions in these environments are often inhospitable. Similarly, while low-elevation areas can provide a relatively mild winter climate, these areas may be less productive during summer when increased temperatures dry out forage more quickly. Rather than stay resident in any one area, migration and the movement between seasonally productive areas has evolved as a behavior that can increase individual fitness, survival, and reproduction.

Residency refers to individuals that are non-migratory and occupy the same seasonal ranges year-round. For example, some resident mule deer in the Powder River area of southeast Montana spend their entire year in an area of less than 2 square miles. In most instances, annual ranges occur on low elevations, although there are exceptions; some bighorn sheep, for example, have high-elevation resident ranges, remaining over 10,000 feet year-round.

Many of Montana's bald eagles stay in Montana year-round although they may shift their range to exploit different food sources. Waterfowl that have access to open water and food are often able to stay in Montana year-round. Residency behavior can be beneficial when year-round food sources are available and animals don’t need to expend energy migrating to other areas.

While residents and migrants provide two general classifications, most wildlife populations contain a spectrum of behaviors along a continuum between residents and migrants. Many animal populations are "partially migratory" and contain both resident and migrant individuals. In partially migrant ungulate herds, both residents and migrants occupy a shared winter or summer range but occupy separate ranges once migrants transition to other ranges seasonally, while residents remain on the shared range year-round.

Outdoor Report

FWP captured and collared several pronghorn near the Big Hole Valley as part of a statewide migration study. Here's a look at one doe's 80-mile migration.